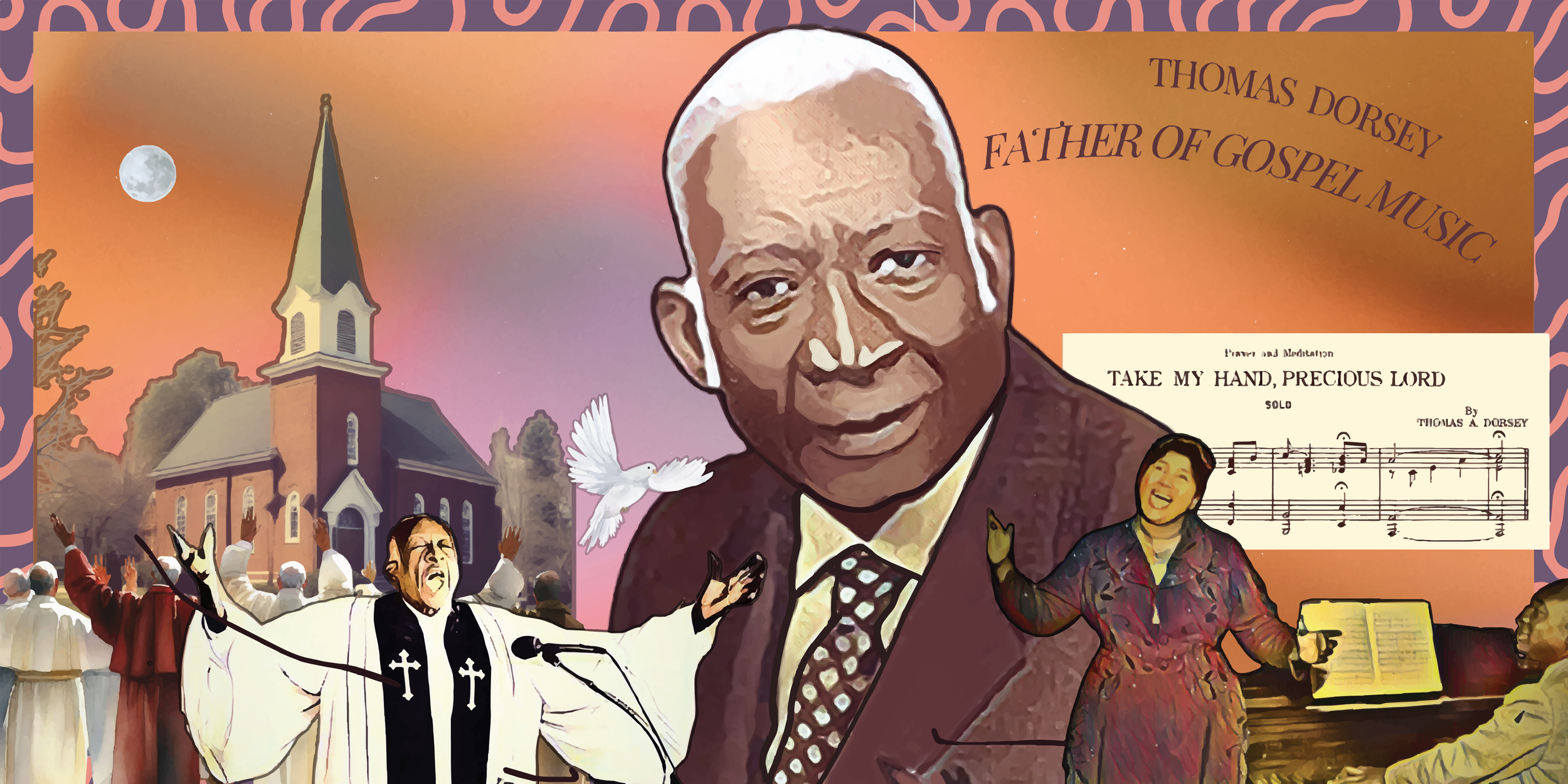

Thomas Dorsey, Mahalia’s Mentor & Collaborator

218 E. 79th St., Anthony SchleicherLearn more about the relationship between two gospel legends

-

In the early 1930s, Black churches in the South Side of Chicago were undergoing a musical revolution. Personal expressions like clapping and stomping along to the music, as well as improvising lyrics and melodies were actively discouraged in the church. They were seen as sinful and hedonistic. At the time, choirs would focus on playing complex arrangements that acted more as a showcase for musical abilities than on the specific spiritual message. Arrangements, like Handel’s “Messiah” and Mozart’s “Hallelujah”, usually came from European composers instead of Black American composers.

Thomas Dorsey changed that dynamic. Dorsey’s background was in the blues; but in 1921, after an inspiring rendition of “I do, Don’t You?” that all changed. Dorsey was inspired by the artistic freedom that gospel allowed its performers. It allowed singers and musicians to infuse more emotion, especially joy and elation, into their performances to move their congregations. At the 1930 National Baptist Convention, unbeknownst to him, Willie Mae Ford Smith sang one of Thomas’ songs “If You See My Savior”. The performance was so popular that Dorsey sold over 4000 records. He knew he had found something that really connected to the people. Shortly after that, Dorsey founded the Thomas A. Dorsey Gospel Songs Music Publishing Company to publish his own sheet music that he would sell copies of. Before the dawn and rise of FM radio in the 40s and 50s, selling sheet music was essential to getting your music heard.

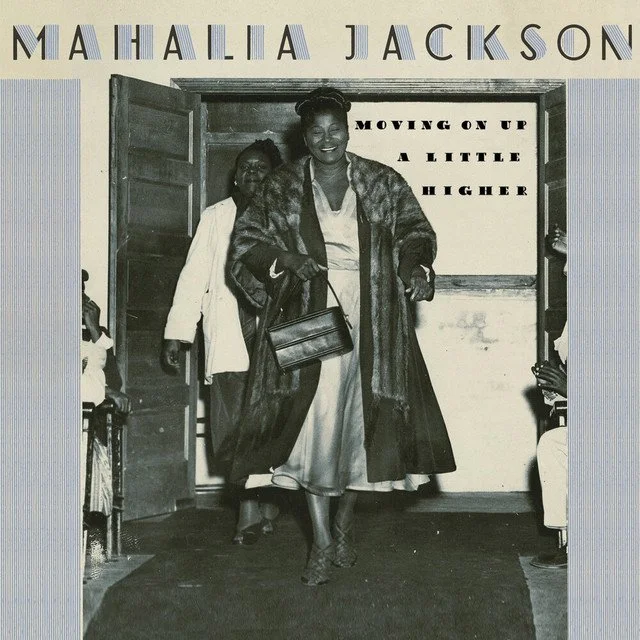

In 1933, Dorsey was appointed to be the Minister of Music and the choir director of the Pilgrim Baptist Church located in the Bronzeville neighborhood of Chicago. He took on more leadership roles within the church and choir, and began mentoring young and aspiring musicians. One of these musicians was a young teenage girl by the name of Mahalia Jackson.

Through Mahalia’s voice, Dorsey found the missing piece between the people and his music. Mahalia would perform Dorsey’s songs on street corners and sell copies of his sheet music for 10 cents a page. The venture was not as financially successful as they had hoped, but the duo had unintentionally created an entirely new music genre: gospel blues solo singing.

Simultaneously, a shift was occurring in Chicago’s Black churches as thousands of newly arrived migrants from the South began to outnumber the old guard in the church. These new parishioners preferred blues over classic European music in services. Now, ministers who just a few years earlier would have never considered changing their music were suddenly open to the idea. Within a matter of months, gospel blues became an established part of Chicago’s Black churches.